The visit of President Joe Biden to Ireland has understandably brought great excitement, nowhere more so than Ballina, County Mayo, his ancestral home in the West. The town has not one, but two presidential claims to fame – it is also where Mary Robinson, President of Ireland from 1990-1997, was born and raised. The University of Galway, also on the West coast, is proud to house the Mary Robinson archive, and to have a strong link with Ballina through its partnership with the Mary Robinson Centre. Her recently restored and extended childhood home, beautifully situated on the River Moy, the Centre is due to open within a year and through this partnership plans to use her archive as a catalyst to inspire others to address the causes she has championed in her career.

This immensely rich archive consists of material relating to Mary Robinson’s work from 1967 to the present and includes material covering her time as a barrister, legislator, senator, professor, President of Ireland, United Nations (UN) High Commissioner of Human Rights, UN Special Envoy for the Great Lakes, UN Special Envoy for Climate Change and El Niño, Chair of the Elders, founder of Realizing Rights - The Ethical Globalization Initiative, and founder of the Mary Robinson Foundation - Climate Justice.

While that task of cataloguing the archive continues, it seems an opportune time to share a selection of items from the archive, some of which have a strong US connection.

Student to Senator

|

| 1981 Seanad election flyer |

At the age of 25, in 1969, she became Ireland’s youngest professor of law, when she was appointed Reid Professor of Constitutional and Criminal Law, at TCD. In the same year she was elected to Seanad Éireann [Ireland’s Senate] as an independent candidate and served as Senator for twenty years, during which time many of the issues she raised and campaigned to reform saw some success - contraception had been legalized, women could now serve on juries and the marriage bar on women in the civil service had been lifted.

President

In 1990, Mary became the first female President of Ireland, and the youngest president at that time. She is widely seen as having revolutionised the role of the Presidency, broadening its scope through her knowledge of constitutional law, developing new political, cultural, and economic links with other countries, reaching out to local communities at home and abroad, and using her platform to bring attention to the suffering of others such as her visit to Somalia in 1992.

Great Britain and

|

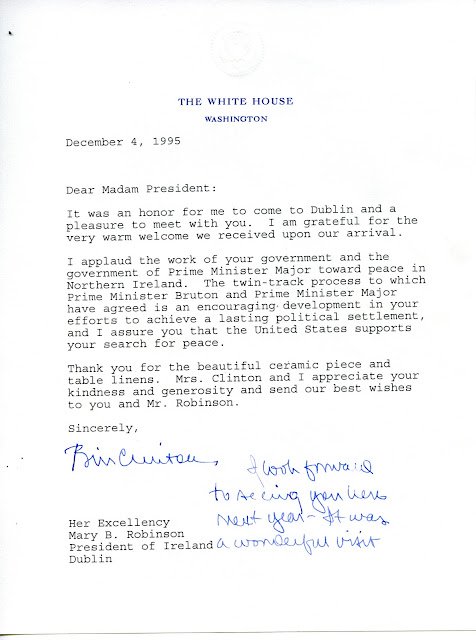

| letter from US President Bill Clinton, in relation to Northern Ireland, 1995 |

U.S. Visit and the Irish Diaspora

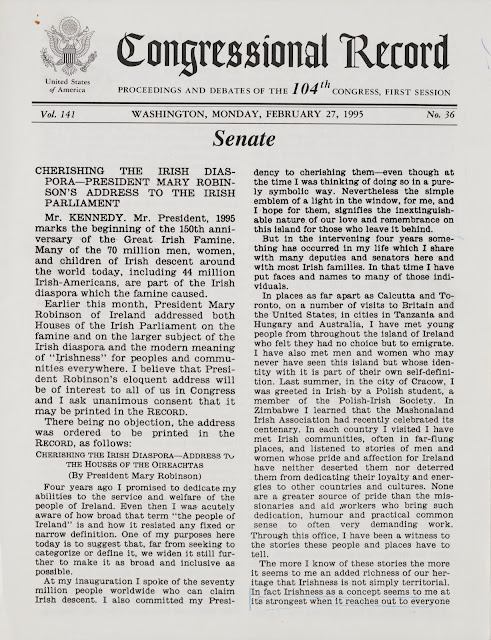

Traditionally seen as the “Taoiseach’s turf” [Taoiseach, meaning "Chieftain" is the term used for the Irish Prime Minister], Robinson became the first Irish President to make an official State* visit to the United States of America while in office, following a public invite from President Bill Clinton, during one of his own visits to these shores. It followed on from her address to the Houses of the Oireachtas [Irish houses of parliament] in 1995 in which she spoke of “Cherishing the Irish Diaspora”. The address, which was positively received by Irish diaspora around the world, was entered into the official Congressional Report of the United States, by Senator Edward Kennedy, brother of Robert and a proud member of the Irish diaspora.

|

| President Robinson's Address "Cherishing the Diaspora" is entered into U.S. Congressional Report by US Senator Edward Kennedy, February 1995 |

|

| Senator Kennedy's response to condolences from President Robinson on the death of his mother, Kennedy matriarch Rose FitzGerald Kennedy, 10 February 1995 |

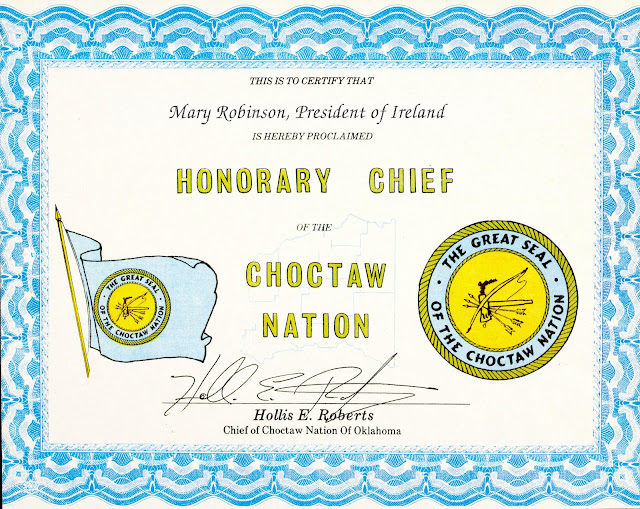

Ireland and the Choctaw Nation

Mary Robinson received many awards throughout her presidency but perhaps none more poignant than that of “Honorary Chief of the Choctaw Nation”. The relationship between Ireland and the Choctaw Nation began in 1847, when the Choctaws collected $170 to support the Irish during the Famine. The gift was significant, considering the Choctaw people had recently been forced to walk the Trail of Tears between 1831 and 1833. Irish President Mary Robinson visited the Choctaw Nation in 1995 to rekindle and re-establish the friendship and thank Choctaws for their aid. In 2020, the Irish people once again honoured that gift, giving back to Native American tribes hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, in memory of the Choctaw Nation’s act of generosity.Robinson was an exceptionally popular president, and halfway through her term of office her popularity rating had reached an unprecedented 93%. She resigned from the presidency a few weeks shy of the end of one term to take up the role of UN High Commissioner of Human Rights and served until 2002. A tireless advocate for justice, she was president of Realizing Rights – the Ethical Globalization Initiative from 2002 to 2010.

The Elders

Planet Pals

|

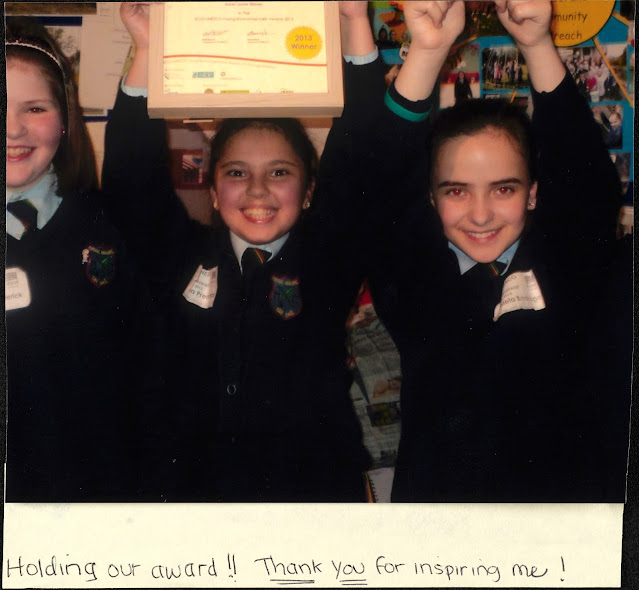

| letter from 10 year old Alicia Premkumar, 2013 |

Some of the nicest items in the archive are letters and drawings from children which, it might surprise some, are carefully kept. In 2013 Mary received a letter from ten-year-old Alicia Premkumar, a pupil of Scoil Mhuire Gan Smál in Carlow, detailing how she had inspired Alicia to set up “Planet Pals” for which she subsequently won “Young Environmentalist of the Year” in the Super Junior Category. Many thanks to Alicia, now a student of Physiotherapy at the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland, for allowing her letter and photograph to be reproduced. Her fellow planet pals were Meadhbh Broderick, Caragh O’Toole (not pictured) and Daniela Besleaga.

Arts

|

| Ticket stub, 1968 |

Medal of Freedom

|

| Medal of Freedom awarded to President Robinson by President Barack Obama in 2009 |

In July 2009, Mary was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour awarded by the United States. Coincidentally, it was also awarded to fellow Elder Archbishop Tutu the same year, and to President Biden in 2017, while he was serving as Vice-President. On presenting her with the award, U.S. President Barack Obama said,

* President Seán T. O'Kelly was invited to the United States of America by President Eisenhower in 1959 and addressed the Joint Meeting of Congress, 18/03/1959. President de Valera attended President John F. Kennedy's funeral in 1963, and made an official visit in 1964 during which he also addressed Congress. President Robinson herself met President Clinton on a private visit in 1993, as did her successor President McAleese in 1998.

President Robinson's 1996 visit was the only official State visit, however. State visits to the United States are formal visits by the head of state from one country to the United States, during which the president of the United States acts as official host of the visitor. State visits are considered to be the highest expression of friendly bilateral relations between the United States and a foreign state and are, in general, characterised by an emphasis on official public ceremonies. State visits can only occur on the invitation of the president of the United States, acting in his capacity as head of the United States. (Official visits, in contrast, can also only occur on the invitation of the president of the United States, though are offered in the president's capacity as chief of the federal government of the United States.)

For further information on the work being carried out to process, preserve and catalogue the Mary Robinson Archive, check out this blog.

%20(1).jpeg)